History

In the 1850's, people in the Sierra City, Downieville, Goodyears Bar & Camptonville areas began vacationing at the Coleman House on Gold Lake. They fished and hunted and sailed on all the nearby lakes. At the same time, locals from Sierra City went on midnight outings to the Buttes. They rode horses to the base of the Buttes where men climbed up & hoisted ladies up with ropes just in time to see the sunrise.

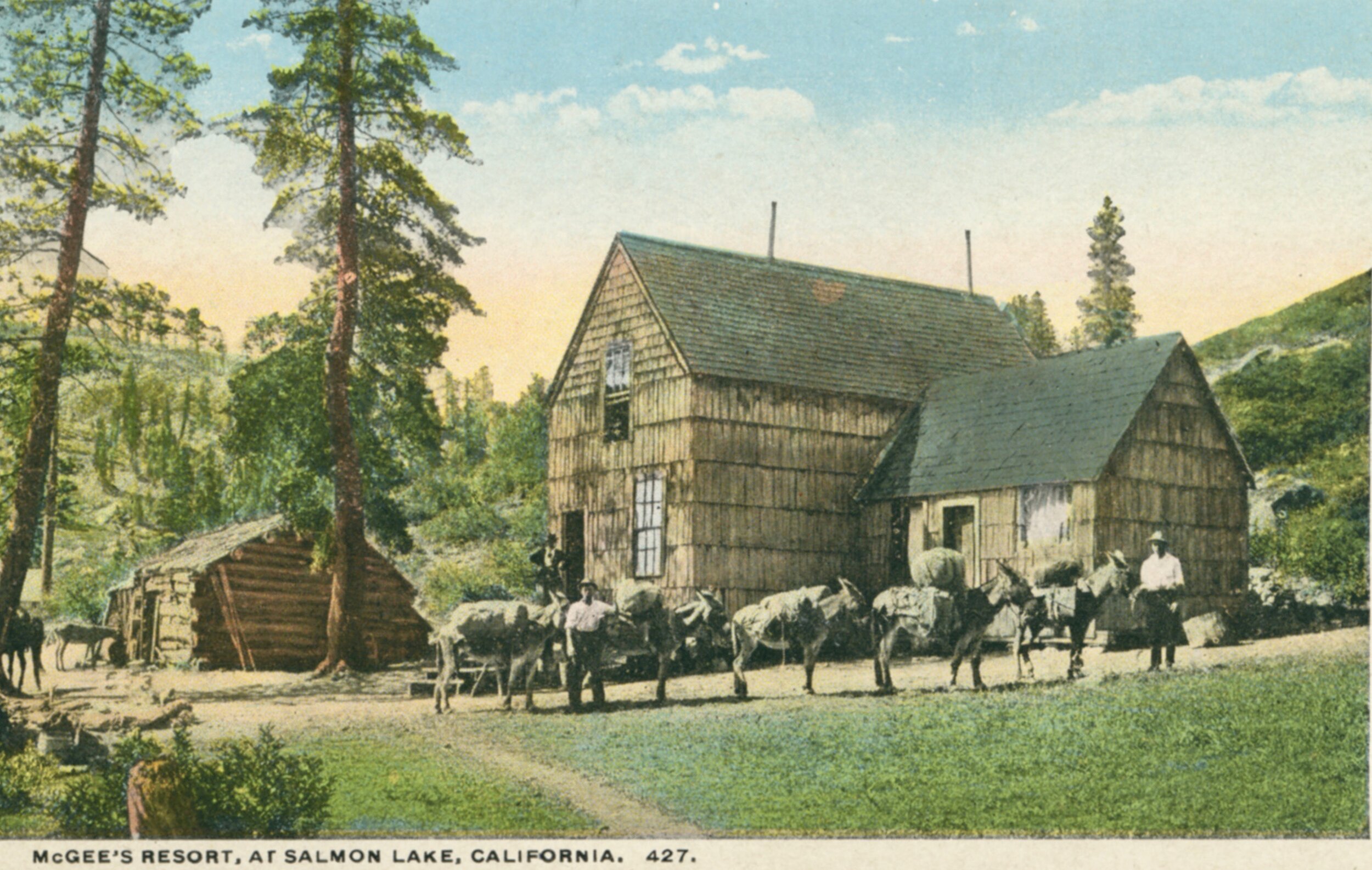

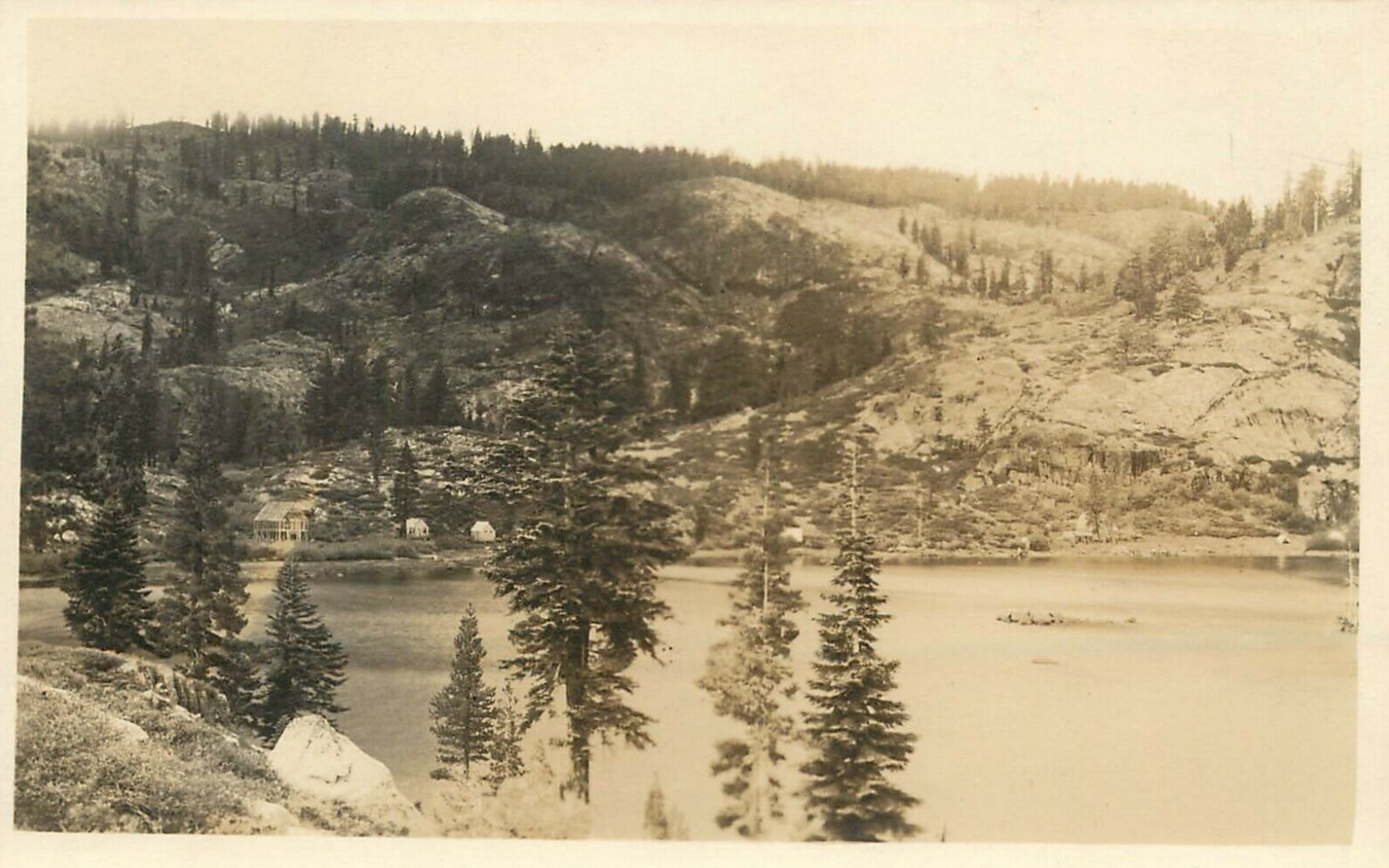

In about 1880, George McGee arrived at Salmon Lake and found gold in the mountains surrounding the lake . He settled down with his wife, built a log cabin and installed a five-stamp mill, powered by a Pelton wheel, to crush the gold-bearing quartz. Mrs. McGee was of a practical mind, and built a resort business to support her husband's obsession with gold. The first lodge building for McGee's Resort was on the northeast shore of the lake, near where the boathouse now stands.

The McGee mining operation was concentrated in three shafts into the ridge north of the Lake. The trail around the lake crosses the tailings from the lowest of these shafts. The other two mines were located above and east of this mine. The ore was then carried on donkeys down a narrow trail and around the lake to the stampmill.

The resort was a thriving business, attracting families from “Down Below,'' who would take the Western Pacific from the San Francisco Bay Area up the Feather River Canyon to Blairsden, and spend the summer at the resort. Papa would, perhaps, be able to join the rest of the family for a week. Some things never change (except that now Mama joins Papa in not having enough vacation time). Many traditions developed, including regular theme parties (culminating in a Grand Masquerade), indulgence of Mr. McGee's pyromania on the Fourth of July, and Mr. McGee's ceremonial delivery of an enormous Forty Niner Flapjack to any child celebrating a birthday breakfast.

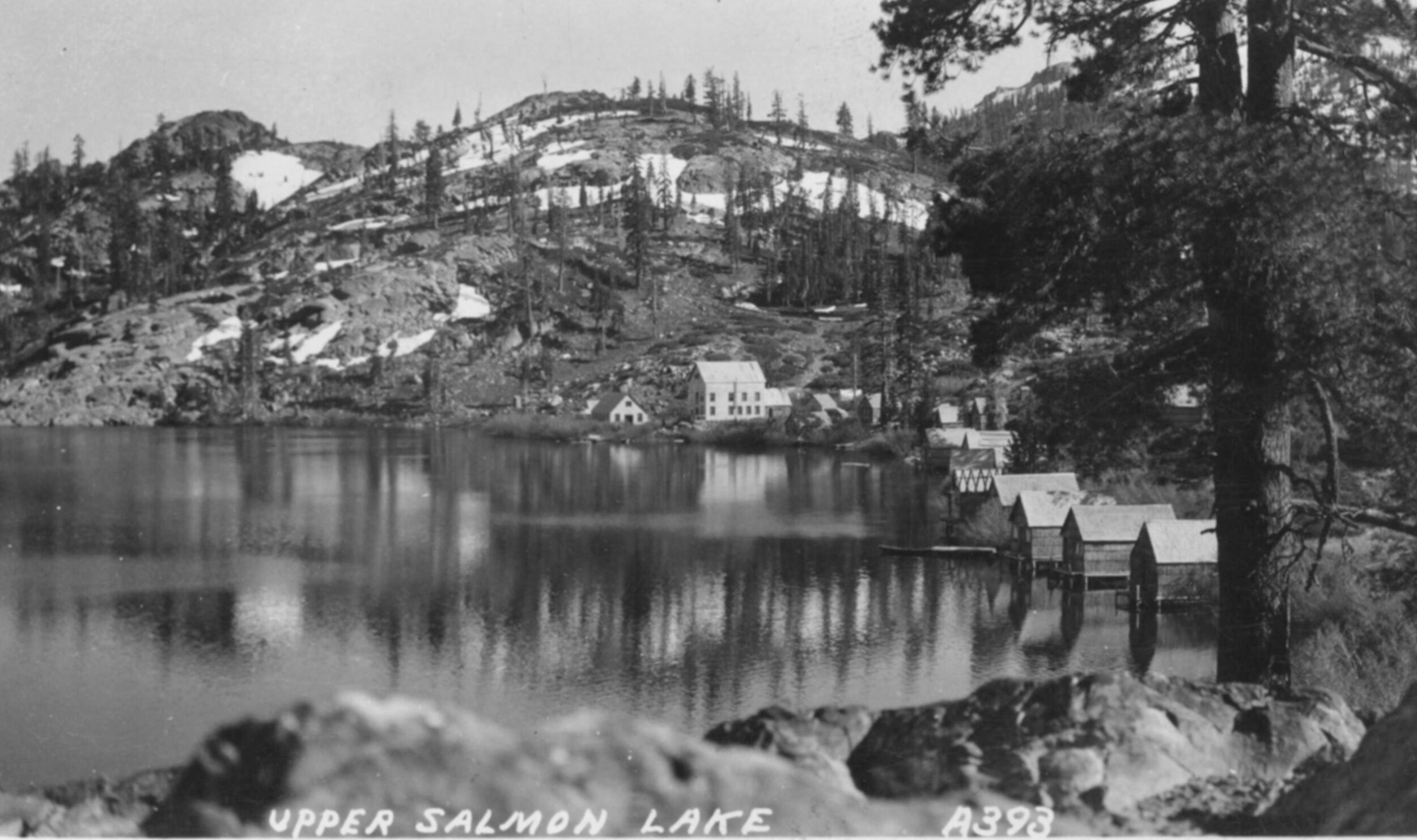

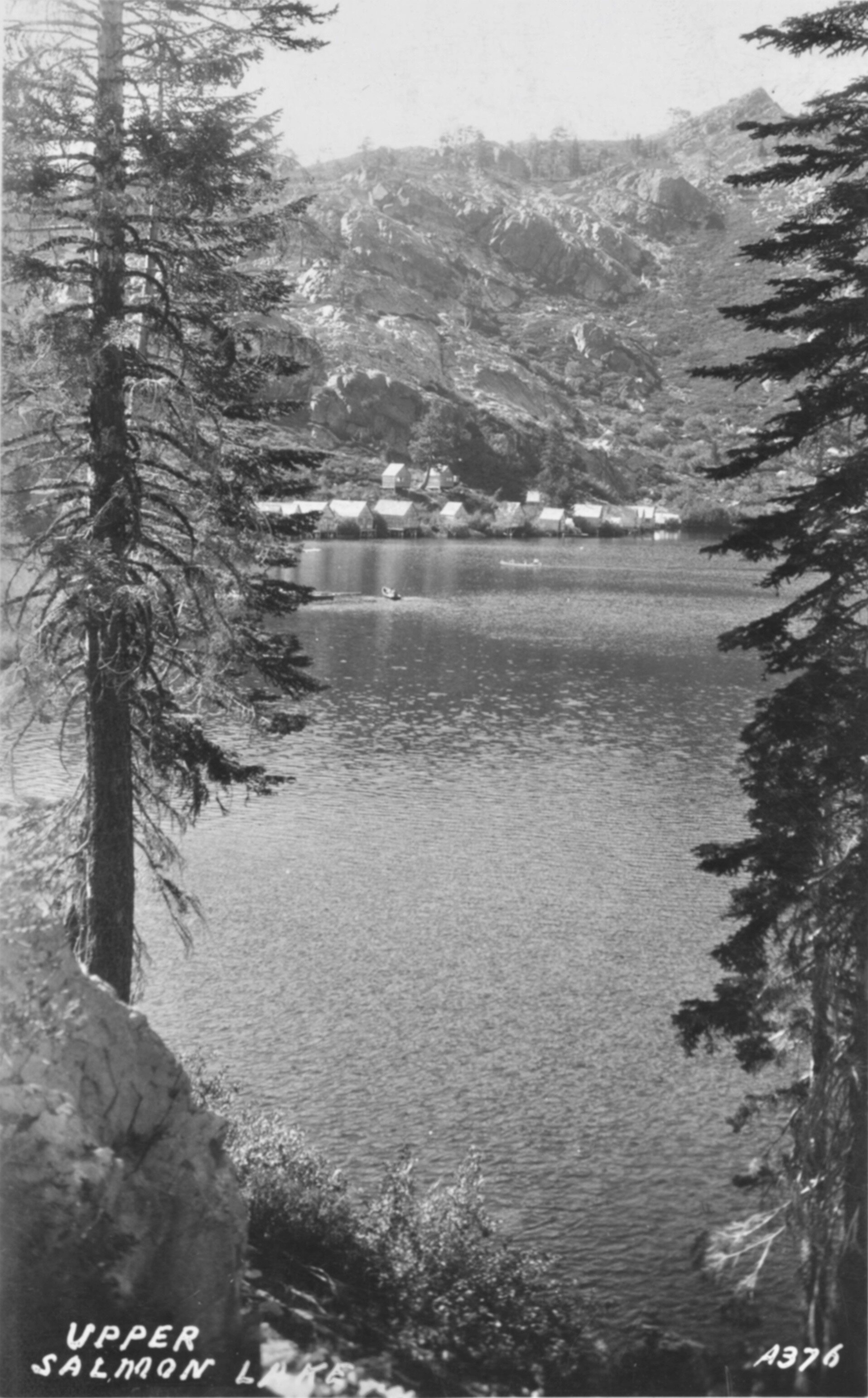

The old lodge eventually burned, and was replaced by new buildings next to the inlet of Salmon Creek, including a dance hall and the core of the present lodge, which was built in the 1920s. The Lodge is a``balloon frame'' building, which means that the wall studs (in this case whole logs) run unbroken from the foundation plate to the rafters. The central beam is an enormous pine log which ran unsupported from one end of the building to the next, and supported the log joists of the second storey (when its sagging became intolerable in the 1960s, a post was added near its center). All of the wood for the building was logged in the area, with the frame made of unmilled timbers, and planks sawn for the floors and walls. The outside was sheathed by sheet metal stamped in a brick pattern, which according to legend was manufactured in Soviet Russia. The main accommodations at the resort were about 20 two-room cabins that stretched along the western shore of the Lake and on the hill behind it. The present hill cabin was built from the best pieces of two of those cabins; it is the same size and shape as the original. There were also a number of tent platforms in the Northwest corner of the Lake.

We don't know how profitable the mining operation was. One suspects that it was sustained by the resort.

During this time there was a competing mining operation, the Pecks Mine, high on the ridge behind the tent cabins. During the 1970s we were visited by an older man who had lived there as a child, while his parents worked the shaft. They had to bring their supplies down from the ridge above, because if they tried to cross the land near the lodge they would attract gunfire. A cable ran down the cliffs above the cabin, powered by a “donkey'' engine, which was used for heavy loads. The old Pecks Mine Cabin has finally returned to the dirt.

During the 1930s the Resort passed into the hands of Charles and Verdabelle Brooks. Charles was an Army veteran who had suffered serious wounds in World War I, and like George McGee was devoted to the search for gold--and was accompanied by a brave and hardworking wife. The couple had three sons, of whom two, Ronald and the son Charles continued the family's association with Salmon Lake. After the older Charles's death, Verdabelle married August Ebbert, another avid miner and tinkerer; August and Verdabelle owned the business until 1959, when they sold the business to the current owners, and retired to North San Juan. During the Brooks/Ebbert years, the back section of the Lodge was built (where the kitchen is now), and a two-story porch was built onto the front. In addition, the old part of the Lakeshore Cabin was built. After “retiring,'' August kept sawing logs for many years in his front yard. Among other things he logged and sawed the cedar “half-logs” that may still be seen in the walls of the Hill Cabin and Showerhouse.

Before PG&E came, there was intermittent electric power generated by the Pelton wheel. The penstock feeding the wheel ran across the ground from Horse Lake, whose level was raised a couple of feet by a dam. In the evenings Ron would hike up to the outlet, remove the board at the top of the pipe, allowing water to flow down to wheel. The wheel would turn and the lights in the lodge would glow for a couple of hours, until the water level in Horse Lake fell below the head of the penstock...and the lodge lights would dim to darkness.

The electric power grid came to Salmon Lake during those years as well. The Plumas Sierra Rural Electric Cooperative was expanding in eastern Plumas and Sierra Counties, and there were rumors that the co-op would expand its territory into the the North Yuba River country. Perhaps in response to that threat, the Pacific Gas and Electric Company extended its grid up the Yuba, ending in the run of wire across the pine forests and granite domes at the top of the Salmon Creek drainage. Ron Brooks recalled the excitement when the crew finally got to Salmon Lake. Dynamite was required to bore the hole to hold the power pole atop the peak just south of the lodge, and the pole itself was hauled by long ropes over the granite cliffs to its present spot.

By the time PG&E arrived, the old penstock was rather rusty, and leaked in many places. In later years Ron remembered that he would carry a coffee can full of wood chips up to Horse Lake, which he would pour into the penstock. As water squirted through the holes in the pipe, the wood chips would jam into place, plugging the holes so long as the pipe was under pressure. When the water ran out, the chips would fall down, and flow out of the bottom of the system. Above is a picture of Ron, taken in the early 1960s, with the old Pelton Wheel.

The water ride at the Disney California Adventures theme park in Southern California includes a large Pelton Wheel, modelled on the famous wheel in Nevada City. The attraction gets some things wrong--the wheel's inventor lived in Camptonville, not Nevada City--but it is absolutely right in at least one respect: it is fed by a rusty penstock, which squirts water all over the place (especially on the unsuspecting clients below). Alas, neither they nor anyone else has a laughing Ron Brooks to pour in wood chips.

In the late 1950s, Verdabelle and August sought a new buyer for the Resort. They approached the Christian family, members of which were then living in Loyalton. The business passed into the hands of these new owners in 1959, where it has remained ever since.

During the early 1960s, the resort continued much as it had earlier. Ron Brooks stayed on for several years, to pass on his knowledge of the resort.

The old wood cabins were increasingly ramshackle, and needed to be removed and replaced. The first removal was accomplished inappropriately by a teenage helper from Loyalton, who had found some dynamite in the attic. After the wood fragments finished settling onto the lake, the helper was dismissed, and future demolition was accomplished in a less spectacular fashion using crowbars. Meanwhile, we visited the tent cabins in Yosemite's Curry Camp, and worked with the Marin County architects, Callister & Paine, to design replacement structures. Charles Brooks, Ron's brother, worked in that office, and delivered drawings of light, high-roofed tent cabins and square cabins with steep pointed roofs, inspired by the ancient stave churches of Norway. During the summer of 1963 construction started, with the stave-church design applied to the Showerhouse, and five of the double-unit tent-cabins located next to a meadow above the lake. These tent cabins remain the core of our business.

To provide water for the new development, a large redwood fermentation vat was purchased from a winery in Lodi, and was hauled in pieces to the top of the hill between the tent-cabins and lakes. There a structure was built, inspired by the stave-church design, but with eight sides, topped by a steep asymmetric octagonal roof, pierced by dormers that would allow the eventual construction of an Owner's Apartment in an attic above the water tank.

As the old shingle cabins deteriorated, they were torn down. Two cabins on a hillside were carefully disassembled, the best timbers taken from each, then reassembled as the Hill Cabin on a site next to the Tankhouse. The hill cabin has the same dimensions and shape as the old cabins. The remaining old cabins were rented for many years to guests from the Old Days. The last of the old structures, the Fish and Game cabin (which had earlier housed state fish biologists) was finally removed in 1976.

In the fall of 1974, work began on a new water system, with construction of foundations for a new tank structure at its present location to the north of the tent cabins. The next summer pipe was laid across the meadow, into the willows and up the gulley to Pecks Cabin. The pipe was 2" steel in 20 foot sections. For tractor transport, a set of scissor-shears was placed in the trailer used for hauling baggage. The pipes were then stacked, six at a time, in the shears, so that they extended over the driver's head in front and just (usually) avoided dragging in the dirt behind. If I remember correctly the contraption only turned over once, and it really didn't hurt that much. When we could go no further with the tractor, the pipes were unloaded and placed in slings, made of cut-up inner tubes, criss-crossed over the shoulders bandolier style so that two people could safely (if with some effort) carry two pipes. Digging trenches through willows turned out to involve more work with a chainsaw than with a shovel. While the willows did provide some shade, they also make wonderful mosquito habitat. It was not a pleasant job.

By the spring of 1976, the new water system was in place, and the old tank structure was transformed into the Tankhouse Cabin. A mill in Portola sawed cedar planks to finish the walls, an old artist friend of the family stared dreamily into space for hours making shapes with his hands, then built a no-angles-or-bevels-duplicated triangular window to fill the space above the door, an employee designed and built an octagonal table, and the work got done just in time for the first guests. Well, almost in time. We eventually repainted the floor which had still been a tad tacky when the first guests moved in. 1981 saw a major refurbishment of old Cabin 2 (the cabins on the lake were numbered). Charles Brooks led a crew in a project to enlarge the building that his stepfather had built, with such innovations as indoor plumbing, electric heat, and a large deck. The core of the old building is still visible in the downstairs bedroom and the living room; the upstairs and the kitchen and bathroom were new. The Ridge Cabin was built in 1990, while the Boathouse was finished in the mid-1990s. Another major construction project in the late 1990s was a reconstruction of the Lodge, with replacement of roof and siding and the construction of a somewhat larger front porch.

Construction (or reconstruction) will always be a part of our experience. Our buildings are in a harsh environment, with up to 20 feet of snow in the winter, and long exposure to the mountain sun. Things fall apart up here, and we keep working to put them back together, during the five months between the snows. Now in our seventh decade at Upper Salmon Lake, we think we have a pretty good idea about what works and what doesn't. One thing is certain: for it to work, it takes work!

There is, of course, one big piece missing from this history. Salmon Lake Lodge is partly the buildings and the people who have worked and lived here. But it is also the thousands of visitors who have come here, some only once, others for many years. There are many people and families for whom Salmon Lake is a home, and a part of their own histories. While we do not tell these stories (which belong to our friends and guests, not to us), they are indeed a big and very important part of the picture.